Don’t look at the banks to understand the next recession

Banks are some of the earliest companies to report each earnings cycle, and their results can be a harbinger for the rest of the economy.

So far, the banks are flashing some warning signs. Notably, some of the big banks are increasing their loan loss reserves at the fastest pace since the pandemic began.

Today, we’ll explain why banks might be getting ahead of themselves.

Investor Essentials Daily:

The Monday Macro Report

Powered by Valens Research

We’re wrapping up the busiest part of earnings season, and as always, some key themes emerged as businesses reported first-quarter numbers.

So let’s take a moment to look back at the companies that kicked it off… the banks. One of the big stories for banks this earnings season was bigger-than-expected loan loss reserve builds.

Loan loss reserves help banks lessen the hit they take if defaults occur. Banks estimate what they’ll need if there are a lot of defaults and put this money into reserves as a cushion. In the fourth quarter, Bank of America (BAC) and JPMorgan Chase (JPM) added $403 million and $1.4 billion to their loan loss reserves, respectively.

That’s the most either bank has added since March 2020. It’s a sign that banks are preparing for tougher times ahead. As we get deeper into 2023 – and even into 2024 – we’ll likely face a mild recession.

This also means credit losses as the Federal Reserve seeks to cool down the economy. These bigger reserves might have some investors spooked. Folks are worried they’re a sign losses could be worse than previously expected. They shouldn’t be.

Today, we’ll take a deeper look at the credit environment. We’ll explain why a looming recession doesn’t need to be a catastrophe. And we’ll share why banks may be overestimating the level of reserves they need.

Reserves are like a security blanket for banks. Banks take reserves because they expect losses from overextended borrowers once boom times cool off. This happened during the Great Recession. Aggregate bank reserves ballooned from $45 billion in 2008 to more than $900 billion in January 2009.

However, there’s one major difference now. Corporate and consumer credit trends are actually pretty healthy. The next recession doesn’t need to be like the bloodbath of 2008… Bank of America, JPMorgan, and many others may be smartly padding reserves now so they can juice returns later.

When it comes to understanding if banks are actually in trouble, we need to look at how healthy their customers are. If banking customers are starting to sweat, that can be a leading indicator for what’s to come.

Trends in this data show us where the economy is headed next. One of the most important data sets is consumer credit delinquency rates. It measures the rate of consumer loans that are past due.

High delinquency rates mean consumers are having a hard time paying their bills on time. And that could lead to banks struggling to collect their debts. Consumer credit delinquencies are historically low today.

Consumer credit is healthy today. And that’s helping folks weather the ongoing storm of the higher interest rates. It’s the same story for commercial and industrial (C&I) loans.

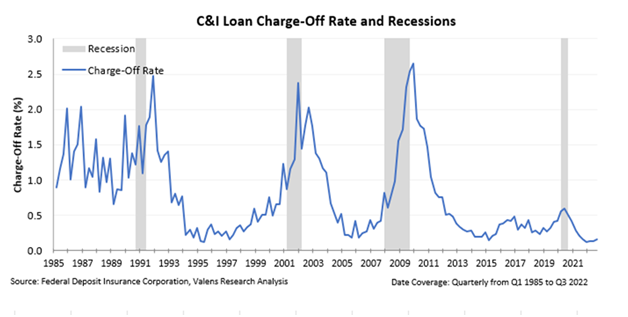

Businesses are another huge part of a bank’s customer base. C&I loan charge-offs are a useful way to understand how bad default rates are for those businesses. They’re what’s called a lagging indicator, meaning a spike in C&I charge-offs usually indicates we’re already in a recession.

C&I loan charge-offs rose in each of the past four recessions. They usually surpass 2%… although they only reached about 0.5% in 2020 due to government stimulus. Today, they’re historically low.

The C&I loan charge-off rate is rising modestly. However, it’s still low today… way below 2%, and with plenty of room before it reaches 0.5%. C&I companies are doing fine as interest rates rise.

This is all good news for the U.S. economic outlook. Banks are healthier than their reserve builds imply. There isn’t going to be a mass wave of defaults anytime soon. Loan loss reserves may be intentionally too high.

The Fed is seeking to cool off inflation. It will tip us into a recession. That doesn’t mean it has to be a deep one

Best regards,

Joel Litman & Rob Spivey

Chief Investment Strategist &

Director of Research

at Valens Research