Holistic investors have changed their strategy this year thanks to the displaced credit market

The first public company in history was quickly followed by the first activist investor in history.

Today’s highlighted investor is following in that activist investor’s footsteps and his time tested approach.

Using GAAP as-reported financial metrics, the investments in this fund’s portfolio make it look like he might not be going after the right companies to create value.

In reality, UAFRS-based financial metrics show how this activist is buying quality companies that just need improved execution to see significant upside.

In addition to examining the portfolio, we’re including a deeper look into the fund’s largest current holding, providing you with the current Uniform Accounting Performance and Valuation Tearsheet for that company.

Investor Essentials Daily:

Friday Uniform Portfolio Analytics

Powered by Valens Research

Carl Icahn, one of the investment greats, was recently on Bloomberg talking about his investment strategy during and since the pandemic.

During the interview, Mr. Icahn talked about his successful recent activism efforts. Two examples of his initiatives in this realm were when he made changes at FirstEnergy (FE) and Bausch Health Companies (BHC).

He also shed some light regarding the current impact inflation has on investing and his outlook in this area.

Considering the content of the interview, we thought it would be worthwhile to refresh our analysis on Icahn’s strategy and fund.

Investors disagreeing with management and trying to change the business is as old as the public company itself.

Literally, the first publicly listed company in the world had an activist shareholder.

The Dutch East India Company, also known as the VOC, was the first modern publicly traded company. It was a revolutionary idea at the time.

Normally investors would finance individual trade journeys by merchants, hoping to gain on the cargo they brought home. But this brought significant risk for investors.

There was risk of disease or piracy or bad weather causing the journey to fail. And even if the cargo made it home, investors had to contend with the risk that the value of the cargo on the open market would be weaker than anticipated.

To reduce the risk for investors, and thereby reduce the cost of capital, a solution was proposed. Investors and merchants would pool their investment in one company, which would grant all investors, both active business participants and passive investors, limited liability.

If investors wanted to get out of their investment, they couldn’t force the company to buy them out. The capital contribution was permanent. Instead, they had to sell their interest, or a portion of it, on an exchange created expressly for this purpose, the Amsterdam Stock Exchange.

The company could finance multiple expeditions, and also manage the volume of spices and other goods that were sold over time, to manage supply and demand. And since a single investor couldn’t force the company to change its course by pulling their capital and demanding liquidity if they disagreed, there was higher visibility too.

Or at least that was the intention.

Almost immediately after the company was created in 1602, one of its largest shareholders, Isaac le Maire, began to have issues with the company. He was originally the governor of the VOC, but after being pushed out for some questionable actions of his own, he started to raise issues with the corporate governance and competitive issues of the VOC.

After being pushed out of the VOC, he started selling VOC shares short, the first ever instance of a person selling a company’s stock short, betting it would go down.

He went on to file a petition raising concerns about the VOC’s corporate governance in 1609.

One of his key issues was how the company’s capital was being stewarded. The company was originally only supposed to exist for 21 years, specifically to focus on East Indies trade.

He believed that the board of directors was trying to structure the company to keep investors locked up for longer than expected originally, and to invest away from its originally stated goals.

In reality, his arguments were largely founded on his own resentment of being pushed out of the firm. But opening the conversation led to a greater revolt in 1622, where shareholders came after the board and company for questionable accounting practices.

Le Maire’s strategy of using his shareholdings to bring attention to key issues he felt needed to be resolved was the first example of shareholder activism, but certainly wouldn’t be the last.

Shareholder activism became something that most investors didn’t think much about over the next 350 or so years, until the late 1970s and early 1980s. Then, as capital markets became more open, two investors began to make a name for themselves by bringing it back.

T. Boone Pickens and Carl Icahn became very well known in the 1980s for being what was termed “corporate raiders.” They’d build big positions in companies and either attempt to buy them, get them sold, or otherwise try to force management to unlock value.

Icahn made a name for himself in 1985 when he took over Trans World Airlines (TWA), and then sold TWA for parts to pay down the massive leverage he took on to acquire the company.

Since then he has committed himself to numerous activist campaigns. He has blocked takeovers he felt were value destructive such as Mylan Labs’ acquisition of King Pharmaceuticals in 2004.

He sought to unlock value in companies that he viewed as being mismanaged or misunderstood by the market, like getting eBay to spin off PayPal in 2014.

He attempted to stand up for shareholder rights in the midst of Michael Dell’s attempt to take Dell private, believing the company was being undervalued.

Icahn has spent over 35 years understanding that sometimes a shareholder needs to be vocal to unlock value in a business, following the path le Maire blazed in the early 17th century.

Sometimes that activism means calling attention to how mispriced a company is, sometimes it means pushing the company to undertake a new strategy to unlock value. Icahn has used all those paths, and continues to at age 84.

Icahn’s goal is to find companies the market misunderstands and that are just not operating as well as they could be, and to help fix the issue.

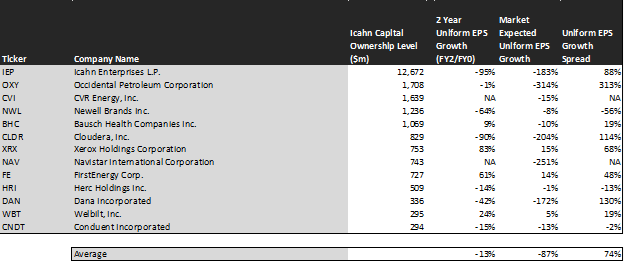

We’ve conducted a portfolio audit of Icahn’s top holdings, based on his fund’s most recent 13-F.

We’re showing a summarized and abbreviated analysis of how we work with institutional investors to analyze their portfolios.

Unsurprisingly, for the most part, Icahn appears to be steering the portfolio to companies that Uniform Accounting metrics highlight are completely misunderstood by the market, and have higher potential than the market and as-reported metrics imply.

Because Uniform Accounting metrics do a better job of identifying real corporate performance than as-reported distorted metrics do, UAFRS is more likely to help explain what Icahn is seeing.

Even though Icahn is often looking to change these companies, he’s trying to find companies that are not completely worthless as is. UAFRS makes that apparent.

See for yourself below.

Using as-reported accounting, investors would think Icahn was truly targeting terrible companies to turn around.

On an as-reported basis, many of these companies are poor performers with returns below 5%, and the average as-reported ROA is 1%. These companies aren’t making any money.

In reality, even after a rocky 2020, the average company in Icahn’s portfolio returns around cost-of-capital returns.

Once we make Uniform Accounting (UAFRS) adjustments to accurately calculate earning power, we can see that the returns of the companies in Icahn’s portfolio are much more robust.

These aren’t broken down turnarounds, these are decent companies that are misunderstood that Icahn can either help focus on improving more, or he can call attention to how they’re mispriced and unlock that value.

Once the distortions from as-reported accounting are removed, we can see that Bausch Health (BHC) doesn’t have a 3% ROA, it is actually at 37%. This is one of the companies Icahn chose to take an active role in, and it has paid off.

Similarly, Newell Brands’ (NWL) ROA is really 24%, not 4%. Icahn sees a healthy, cash-generating business he can call attention to.

The list goes on from there, for names ranging from FirstEnergy (FE) and Welbilt (WBT), to Conduent (CNDT) and CVR Energy (CVI).

If Icahn was focused on as-reported metrics, the fund would never pick most of these companies, because they look like bad companies and poor investments.

But to find companies that can deliver alpha beyond the market, just finding companies where as-reported metrics misrepresent a company’s real profitability is insufficient.

To really generate alpha, any investor also needs to identify where the market is significantly undervaluing the company’s potential.

Bridgewater is also investing in companies that the market has low expectations for, low expectations the companies can exceed.

This chart shows three interesting data points:

– The first datapoint is what Uniform earnings growth is forecast to be over the next two years, when we take consensus Wall Street estimates and we convert them to the Uniform Accounting framework. This represents the Uniform earnings growth the company is likely to have in the next two years.

– The second datapoint is what the market thinks Uniform earnings growth is going to be for the next two years. Here, we are showing how much the company needs to grow Uniform earnings by in the next 2 years to justify the current stock price of the company. If you’ve been reading our daily and our reports for a while, you’ll be familiar with the term embedded expectations. This is the market’s embedded expectations for Uniform earnings growth.

– The final datapoint is the spread between how much the company’s Uniform earnings could grow if the Uniform Accounting-adjusted earnings estimates are right, and what the market expects Uniform earnings growth to be.

The average company in the U.S. is forecast to have 5% annual Uniform Accounting earnings growth over the next 2 years. Icahn’s holdings are forecast by analysts to significantly lag that, shrinking by 13% a year the next 2 years, on average.

Icahn is finding companies that are struggling to execute on growth and pushing them to improve.

But on average, the market is even more pessimistic than forecasts imply is warranted. The market is pricing these companies to see earnings shrink by 87% a year.

While these companies are not growing, they are intrinsically undervalued, as the market is mispricing their growth by 74% on average. Even if Icahn isn’t successful, he’s got a safety net.

If Icahn’s activism can drive these companies to improve their operations, or at worst, draw attention to how undervalued they are, these companies are likely to rally significantly. Without Uniform numbers, the GAAP numbers wouldn’t show this reality.

One example of a company in Icahn’s portfolio that has growth potential that the market is mispricing is Occidental Petroleum (OXY). OXY’s analyst forecasts have 314% Uniform earnings shrinkage built in, but the market is pricing the company to have earnings shrink by only 1% earnings each year for the next two years.

Another company with similar dislocations is Dana Incorporated (DAN). Expectations are for market average shrinkage of 172% growth in earnings. However, the company is actually forecast for Uniform EPS to shrink by 42% a year. While expectations are not great, if it can deliver higher growth than expected, there’s more upside.

Yet another is Cloudera (CLDR). CLDR is priced for a 204% decline in Uniform earnings, when they are forecast to shrink by 90% a year.

Unsurprising considering how for some of these companies Icahn’s plan is to make significant changes, there are a few companies in the portfolio that look misplaced.

For the most part, Icahn’s ideas look like undervalued stocks with opportunities for a savvy activist. It wouldn’t be clear under GAAP, but unsurprisingly, Uniform Accounting and a system built to deliver alpha see the same signals.

Icahn Enterprises L.P.’s Tearsheet

As Icahn’s largest individual stock holding, we’re also highlighting Icahn Enterprises’ tearsheet today.

As the Uniform Accounting tearsheet for Icahn Enterprises L.P. (IEP:USA) highlights, Icahn’s Uniform P/E trades at -33.0x, which is below the global corporate average valuation of 23.7x and its own historical valuation of -19.9x.

Low P/Es require low EPS growth to sustain them. In the case of Icahn, the company recently had an 18% Uniform EPS growth.

While Wall Street stock recommendations and valuations poorly track reality, Wall Street analysts have a strong grasp on near-term financial forecasts like revenue and earnings.

As such, we use Wall Street GAAP earnings estimates as a starting point for our Uniform earnings forecasts. When we do this, we can see that Icahn is forecast to see Uniform EPS shrinkage of 99% in 2021 followed by an 18% growth in 2022.

The company’s earnings power is below corporate averages. Furthermore, cash flows and cash on hand falls short of obligations within five years. However, intrinsic credit risk is only 80bps above the risk free rate. Together, this signals a high dividend risk and low credit risk.

To conclude, Icahn’s Uniform earnings growth is well below peer averages in 2020. Also, the company is trading well below peer valuations.

Best regards,

Joel Litman & Rob Spivey

Chief Investment Strategist &

Director of Research

at Valens Research