While the market is talking about inflation, the Fed is thinking about unemployment

While Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell largely received good marks for his keynote speech at this year’s virtual Jackson Hole meeting, many still have reservations about the Fed’s current strategy in dealing with inflation.

For some critics, the central bank’s apparent reluctance to acknowledge that “transitory” inflation may be more lasting than their models suggest is a big reason for concern. They think rampant inflation may force the Fed’s hand to raise interest rates sooner than expected.

However, Chairman Powell has a different goal in mind than inflation, which is guiding his policies today.

Investor Essentials Daily:

The Monday Macro Report

Powered by Valens Research

We think it might be useful to look back at this year’s presentation and Chairman Powell’s statements on monetary policy in the context of 2020’s paradigm-shifting Jackson Hole meeting.

When looking at the numbers last week, we said the risk of inflation is overblown. This is partly why Chairman Powell has his sights set on a different target.

In 2020, Chairman Powell laid out a new monetary policy framework based on an idea called “average inflation targeting.” This means the central bank will allow inflation to overshoot its 2% annual target to make up for periods where inflation was less than 2%.

Traditionally, monetary policymakers deferred to the idea that decreasing unemployment past a certain threshold, known as the “natural rate” of unemployment, would inevitably lead to higher inflation, a relationship made famous by the Phillips Curve model.

According to this logic, as unemployment declined and more people entered the workforce, demand and spending in the economy would increase, pushing up prices.

As a result, the Fed’s historical strategy for a recession recovery was to raise interest rates as unemployment rates grew smaller and smaller. This would cool the economy down and prevent inflation spikes.

The problem is with more research, the data supporting this model has become shaky, leading Chairman Powell and others at the Fed to abandon it in favor of the new framework. By allowing for a period of inflation above 2%, the Fed is focused on getting as many people back to work as possible before raising interest rates, ensuring a smoother recovery.

Looking at the Fed’s actions through the context of the new framework, it is pretty clear why Chairman Powell is still not overly worried about inflation and more concerned about the labor market.

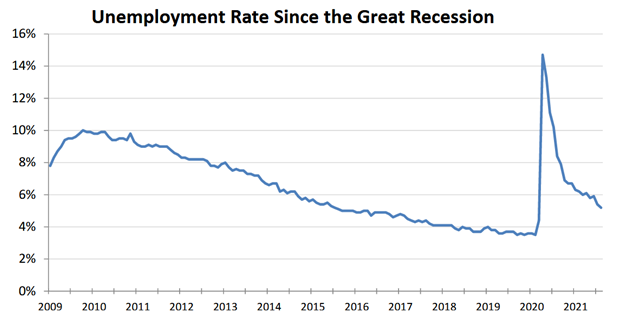

Unemployment rates in the U.S. have fallen below 6%, an impressive improvement considering the pandemic-induced recession’s severity that led to unemployment rates spiking above 14% in April 2020.

The lowest wage-earners were benefiting the most from a strong economy and labor market in 2019. However, there is still more progress to be made to get unemployment back to historical pre-pandemic lows of less than 4%. The target for the Fed policy is reversing the damage of the pandemic.

To put it bluntly, Chairman Powell feels his work on the labor market side is still far from over.

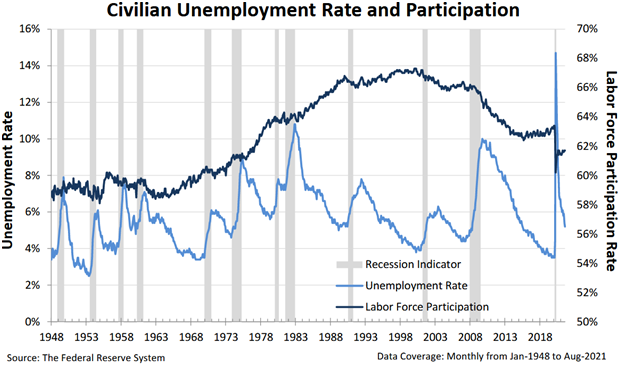

Much discussion has been made about “help wanted” signs at restaurants and labor shortages at businesses across the U.S. This can be seen in the labor force participation rate remaining depressed at levels lower than any time since the mid-1970s, as the dark blue line in the chart below shows.

Women entered the workforce en masse in the 1970s, and this depressed labor participation rate is historic when viewed in context.

The slow recovery in labor force participation may have to do with many factors. These include continued fear of catching the coronavirus, elevated savings from generous government assistance, and a massive wave of retirements over the past 18 months.

In any case, the decline has the Fed worried, and for a good reason.

Intuitively, a nation’s output, measured by metrics like GDP is a function of how much can be produced with a given amount of capital and labor.

With a lower labor force participation rate, which measures the economy’s active workforce, fewer workers are available to create productive output. If the productivity of the remaining workers doesn’t make up for this loss, the result will be a slower-growing economy.

All of this means that as Chairman Powell fights to get unemployment rates trending lower and participation rates trending higher, monetary policy is likely to stay loose, keeping interest rates historically low and valuations in the stock market high.

Best regards,

Joel Litman & Rob Spivey

Chief Investment Strategist &

Director of Research

at Valens Research